Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center’s constitutional literacy adviser, looks at the FBI and Attorney General’s role in deciding to press charges in high-profile cases, which can suddenly gain a lot of visibility when a criminal investigation is aimed at a prominent political figure.

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

“Although there is evidence of potential violations of the statutes regarding the handling of classified information, our judgment is that no reasonable prosecutor would bring such a case…In looking back at our investigations into the mishandling or removal of classified information, we cannot find a case that would support bringing criminal charges on these facts….There is evidence that they were extremely careless in their handling of very sensitive, highly classified information. For example, seven email chains concerned matters that were classified at the top secret, special access program at the time they were sent and received.”

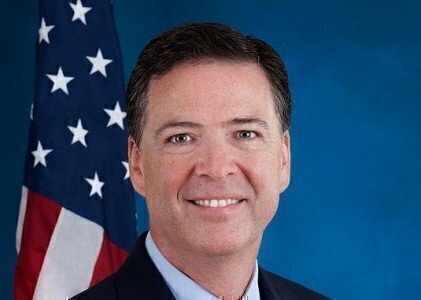

– Excerpt from a statement that FBI Director James B. Comey made during a news conference on Tuesday about the conclusion of the federal investigation of how Hillary Clinton and her aides used e-mail servers for communicating messages during her time as Secretary of State.

“The major functions of the Bureau include…investigate violations of the laws of the United States and collect evidence in cases in which the United States is or may be a party in interest, except in cases in which such responsibility is by statute or otherwise specifically assigned to another investigative agency.”

– Excerpt from the FBI’s statement of its mission, as shown on the Justice Department’s official website.

WE CHECKED THE CONSTITUTION, AND…

From the beginning of the new national government in 1789, the president has had an attorney general to act as a legal adviser. For a time, actually prosecuting criminals was a sideline for that officer. Private lawyers were hired to do that task, and that approach grew – by the end of the Civil War – to be very expensive. In 1870, Congress decided to create a Department of Justice, with its own staff of lawyers, and, from then on, it was the chief law enforcement agency in the presidential Cabinet.

While the department and all of its sub-agencies do work under the president’s leadership, and that can raise the prospect that politics will enter into the department’s work, most attorneys general have tried to keep a wall of separation between how and who they prosecute, on the one hand, and the politics of law-and-order, on the other. The public’s perception of justice has depended on that wall, attorneys general have said, over and over again.

From the attorney general, down through the ranks of the department’s employees and sub-agencies, the tradition of political impartiality is taught as a matter of professional ethics. In fact, every lawyer in the department each year must attend a refresher course in legal ethics.

As an integral part of the department, the Federal Bureau of Investigation is supposed to share in that tradition. From its creation in 1908, the FBI has cultivated a reputation of trust with the American public; in fact, it is one of the most successful federal agencies in maintaining the esteem of average Americans. It is not at all surprising that tourists made their way, in droves, to the FBI’s public exhibits in Washington, D.C., of its work.

But the public may not always understand that the FBI does not have the job of deciding who should, or should not, be prosecuted for crime. It was created to do investigations – period. When it finishes one of its probes, it can and usually does make recommendations, but someone else has the job of deciding what to do with the results of those investigations – an actual prosecutor.

The Supreme Court has raised the role of prosecutor to a level of eminence that is close to that of a judge. Judges have long been immune to being sued for the way they perform their tasks on the bench, and the Supreme Court – in a famous decision in 1976, in the case of Imbler v. Pachtman -- declared for the first time that prosecutors, too, are almost entirely immune for the choices they make about filing charges and pursuing them at trial.

Of course, even the Supreme Court cannot insulate prosecutors from public – and political -- criticism about how they perform their jobs. And, if a given prosecutor abuses the office, by going outside the scope of their official duty, they are subject to legal claims of “malicious prosecution.’ But, because their normal legal immunity is so expansive, it is very difficult to prove the misuse of power in a given case. The Supreme Court has made clear, repeatedly, that this broad immunity is designed to encourage behavior by prosecutors that will keep the public’s trust while at the same time maintaining prosecutors’ independence.

All of these questions of professional responsibility and legal immunity of prosecutors can suddenly gain very high political visibility, especially when a criminal investigation is aimed at a prominent political figure. No matter how impartial the FBI may be in conducting such an investigation, or a federal prosecutor may be in deciding what to do with the results of an FBI investigation, there is almost no way to avoid political controversy in such a case.

FBI Director James B. Comey, and his ultimate boss at the Justice Department, Attorney General Loretta Lynch, have understood these political realities. No matter what course the FBI investigation took into the e-mail controversy at the State Department, and no matter what will be done with the results of that probe, each of them understood that they were functioning on a public stage, made even more intensely public by the fact that this is a presidential election year, and one of the two candidates was the central figure in the investigation – former Secretary of State Clinton.

Legal conclusions have already been drawn by the FBI’s team, and Attorney General Lynch has already said that she would defer to whatever the Bureau recommended to her. That will be the judgment that emerges from the Department of Justice. Although both of them may be summoned before Congress to answer questions, they are sure to stand by the choices they made or will make. Then, in November, it will be up to America’s voters to have a say in the matter, if they think it bears upon their political choice.