Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center’s constitutional literacy adviser, looks at two rights under consideration as stars in college sports have grown increasingly upset with their economic status in big-time college sports.

“The NCAA’s argument that videogame developers’ use of student-athletes’ names, images, and likenesses is protected under the First Amendment was rejected by the Ninth Circuit Court earlier in this litigation…”

– Excerpt from a decision last Friday by U.S. District Judge Claudia Wilken of Oakland, Calif She ruled that college student-athletes have a legal right to a share of the revenue that National Collegiate Athletic Association’s member colleges earn from the sale of licenses to use the student-athletes’ names, images, and likenesses on television and in other media.

“Video game developer Electronic Arts had no First Amendment defense against the right-of-publicity claims of former college football player, Samuel Keller…EA’s use did not qualify for First Amendment protection as a matter of law because it literally recreated Keller in the very setting in which he had achieved renown.”

– Summary by the Ninth Circuit Court of its 2013 decision to which Judge Wilken referred, at an earlier stage of the NCAA case. The Circuit Court found that a “right of publicity” prevailed over a First Amendment free-expression claim. A dissenting judge argued that the videogame developer should have First Amendment protection.

WE CHECKED THE CONSTITUTION, AND…

For nearly four decades, there has been a running legal battle between the Constitution’s First Amendment and a right created under state law for celebrities and others who gain public prominence . Obviously, the news media and other entities that purvey information have a keen interest in following the careers of those high-visibility personalities. They have a First Amendment right to do so, but it can be limited, and has been, during the 37 years since the Supreme Court ruled that a news organization had covered too much of the daredevil act of a “human cannonball.”

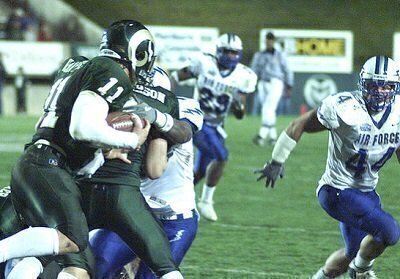

This conflict between a constitutional right and a private right has been playing out in recent years as stars in college sports have grown increasingly upset with their economic status in big-time college sports, especially the revenue-rich football and basketball programs of major universities and competition conferences.

That grievance led them to sue the National Collegiate Athletic Association in an antitrust lawsuit, claiming a share of the revenues that the NCAA brings in by selling to TV networks and others – including videogame producers – the right to use the likenesses of the players as they perform on the field or court. They won in the first round in that case last Friday in a federal court in California.

But they have been pursuing other ways to derive some income based on publicity about their performances, and that is where the First Amendment vs. private right clash has been most apparent. That also was an issue in the players’ antitrust case against the NCAA, but that is no longer at stake in that case because a federal appeals court sided with the private right, not the First Amendment. That ruling is a part of the continuing conflict in the courts over rights.

As individuals who acquire a form of public notoriety or stature, star college athletes are allowed to claim a “right of publicity” to prevent others from profiting from their athletic exploits. This “right of publicity” grows out of a more basic right, the right to personal privacy, and the theory behind it is that individuals have a right to “reap the rewards of their endeavors,” as courts have phrased it.

While it has overtones of a constitutional guarantee, the right of publicity is actually – and only – a creation under state law. As of now, 19 states have passed laws recognizing such a right, and 28 others recognize it under “common law” – that is, as a matter of legal tradition not written down in a specific statute. Thus, if college athletes qualify for that right, it would exist for them across the country, in all but three states.

The Supreme Court has dealt only once with the conflict between the First Amendment and the right of publicity, but that did result in a major precedent. The 1977 case of Zacchini v. Scripps Howard Broadcasting involved a performer – at fairs and carnivals – who had a right of publicity under Ohio state law. Hugo Zacchini’s act was having himself shot out of a cannon.

He objected when a TV station broadcast his entire act, from end to end. He contended in court that this exploited the very activity on which his public reputation depended. The Court agreed, and commented: “Wherever the line in particular situations is to be drawn between media reports that are protected and those that are not, we are quite sure that the first and Fourteenth Amendments do not immunize the media when they broadcast a performer’s entire act without his consent.”

Because the Court did not give any further guidance on where to draw the line between the First Amendment and a state-created right of publicity, it has been left to the lower courts since then to do the balancing. One test that several courts have devised is what is called the “transformative use test.” In recent decisions involving college athletes’ claim of a right of publicity, that test has been decisive, in the athletes’ favor.

Borrowed from a 2001 decision by the California Supreme Court, this legal test is focused on whether the depiction of a performance is simply an imitation of the real-life one, or whether it in fact adds some creative element that transforms it into a new form of expression. A mere imitation gets no First Amendment protection.

As the Zacchini case showed, the individual who has attained celebrity status can make a right of publicity claim against an actual news organization, illustrating how far the right might go. But, lately, college athletes have been making the claim mostly against videogame developers, with a much more likely chance of getting access to a share of profits. Videogame companies create imitations of college games but do so by using easily identified “avatars” who represent real-life athletes doing exactly what has made them famous.

Not only has the Ninth Circuit Court ruled for athletes in that context, so has the Third Circuit Court and the Seventh Circuit Court. As a result, the First Amendment defense against the claim is considerably weakened these days.