Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center's constitutional literacy adviser, looks at comments from retired Air Force General Michael Hayden about possible conflict between the military and a civilian President over controversial orders - a debate triggered by recent comments from GOP candidate Donald Trump.

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

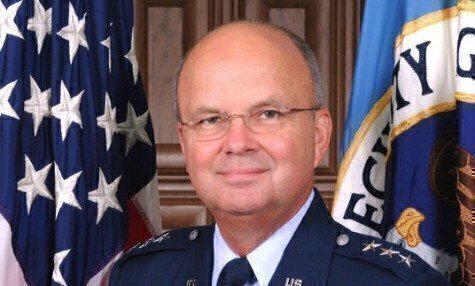

“I would be incredibly concerned if a President Trump governed in a way that was consistent with the language that candidate Trump expressed during the campaign….Let me give you a punchline: If he were to order that [the killing of family members of terrorists] once in government, the American armed forces would refuse to act. You are not required to follow an unlawful order. That would be in violation of all the international laws of armed conflict.”

– Comments by retired Air Force General Michael Hayden, on February 26 during an appearance on the HBO television program, “Real Time with Bill Maher.”

“In view of the specific responsibilities imposed upon me by the Constitution of the United States and the added responsibility which has been entrusted to me by the United Nations, I have decided that I must make a change of command in the Far East. I have, therefore, relieved General MacArthur of his commands….Full and vigorous debate on matters of national policy is a vital element in the constitutional system of our free democracy. It is fundamental, however, that military commanders must be governed by the policies and directives issued to them in the manner provided by our laws and Constitution.”

– Excerpt from an official statement from President Harry Truman on April 10, 1951, announcing that he had dismissed General Douglas MacArthur as the U.S. and U.N. military commander in Korea during the war there, after MacArthur insisted on planning military attacks against China when it was Truman’s policy to try to get China to the bargaining table to negotiate over an end to that war. The firing came after MacArthur not only defied Truman’s military orders, but complained openly about the President to Congress; Truman’s action was one of the most important constitutional developments during that war. WE CHECKED THE CONSTITUTION, AND…

A cardinal principle of government that those who wrote the Constitution held dear was that the American military would always be under the ultimate command of civilian leaders. George Washington, the Revolutionary War commander and the first Commander-in-Chief, was always devoted to the subordination of the military to civilian rule, and he actually put down a rebellion among his officers over the failure of the civilian government to keep military pay current during the Revolution.

When Abraham Lincoln worked his way through a series of field commanders during the Civil War, he did so partly because he found several of them inept, and partly because he wanted to remain in firm control of the military course of the conflict.

America, though, has no more vivid illustration of civilian dominance of military affairs than President Truman’s swift dismissal of General Douglas MacArthur when the general began waging the Korea war on his own terms in 1951, and openly moved ahead with military adventures that Truman felt would frustrate the attempts to get peace negotiations going.

It appears, though, that America might once again find itself in the midst of one of those historic conflicts, if this year’s presidential election should put Republican candidate Donald J. Trump into the White House, as Commander-in-Chief. If Trump were to win the office, and if he were, in fact, to move forward with some of his ideas for waging the war on terrorism, including a return to torture of terrorist suspects and even more brutal strategies for demoralizing them by killing their families, it is reasonable to expect that he would encounter stiff resistance from within his in-house military advisers, without a rebellion by them. But would military commanders actually refuse to obey direct orders from Trump as their ultimate commander?

One can surmise that, even if Trump were to undertake such commands to his military subordinates, there would be many points of resistance within the government to going forward, well before military commanders might resort to open defiance. And one can imagine that a good measure of resistance would come from at least some congressional leaders.

But, assuming the worst-case scenario, is such insubordination out of the question?

Retired General Michael Hayden last week suggested that very possibility, relying on an argument that such resistance would have international law on its side. Perhaps the former leader of the National Security Agency and of the Central Intelligence Agency was trying to reassure himself that the modern development of international war crimes commissions for the punishment of outright violations of the law of nations is now making legitimate the acts of disobedience to orders to commit atrocities.

Although the general added that he was not talking about a coup by the military, his remarks had the rather scary sound of just such a maneuver. It was chilling precisely for constitutional reasons: it is not the function of the military to make a decision that the policy choices of civilian government leaders are outrageous, or even that they violate norms of international law. That is not a military function. It is simply well outside of any norm of constitutional understanding to pretend either that the military is capable of making legal judgments, or that it has been set up to be a player in checks-and-balances.

If Donald Trump in the White House were to set out to lead the country down a path toward authoritarian Executive Branch leadership, then either the existing constitutional order will work to restrain that impulse, or the country will be on its way toward self-destruction.

It is possible, of course, that General Hayden was simply making a rather clumsy attempt to raise the alarm about the direction in which he perceived the presidential election campaign to be moving. Plenty of other people are alarmed about that, but it is not common these days to hear that the solution is a resort to tactics befitting a banana republic.