In a new Vanity Fair article, the magazine claims former White House adviser Steve Bannon warned President Donald Trump that his own Cabinet could remove him by invoking the 25th Amendment. Is that how the amendment actually works?

Without considering the merits of the Vanity Fair article, and just reviewing the Cabinet’s powers under the amendment, the process would be much more complicated than a simple vote by the Cabinet to take away any President’s power in any form.

Without considering the merits of the Vanity Fair article, and just reviewing the Cabinet’s powers under the amendment, the process would be much more complicated than a simple vote by the Cabinet to take away any President’s power in any form.

The 25th Amendment deals with presidential (and vice presidential) succession and disability. It was passed by Congress in July 1965 after considerable public debate and consideration in the House and Senate. It took about 18 months for three-quarters of the states to ratify the amendment.

Link: Read The Full Text On Our Interactive Constitution

Sections 3 and 4 deal with situations where a President may suffer an “inability” or “disability.” The 25th Amendment’s Section 3 allows the President to tell Congress that the Vice President can act as President until he or she is able to resume work.

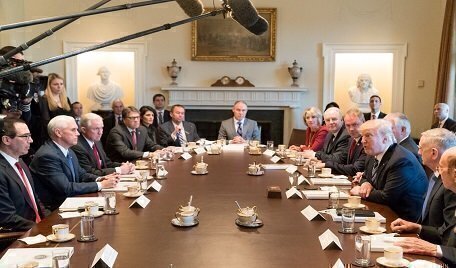

Section 4 is the most controversial part of the 25th Amendment: It allows the Vice President and either the Cabinet, or a body approved “by law” formed by Congress, to jointly agree that “the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” This clause was designed to deal with a situation where an incapacitated President couldn’t tell Congress that the Vice President needed to act as President.

It also allows the President to protest such a decision, and for two-thirds of Congress to decide in the end if the President is unable to serve due to a condition perceived by the Vice President, and either the Cabinet or a body approved by Congress. So the Cabinet, on its own, can’t block a President from using his or her powers if the President objects in writing. Congress would settle that dispute and the Vice President is the key actor in the process.

The potential use of Section 4 to remove a President from office as part of a political dispute is very controversial. And some constitutional observers feel that isn’t the intent behind the 25th Amendment.

On our Interactive Constitution website, scholars Brian C. Kalt and David Pozen explain the problematic process if the Vice President and the Cabinet agree the President can’t serve.

“If this group declares a President ‘unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office,’ the Vice President immediately becomes Acting President. If and when the President pronounces himself able, the deciding group has four days to disagree. If it does not, the President retakes his powers. But if it does, the Vice President keeps control while Congress quickly meets and makes a decision,” said Kalt and Pozen. “The voting rule in these contested cases favors the President; the Vice President continues acting as President only if two-thirds majorities of both chambers agree that the President is unable to serve.”

In May 2017, National Constitution Center president and CEO Jeffery Rosen wrote in The Atlantic about the political nature of an attempt to use the 25th Amendment to remove a President, and not the impeachment process.

“It’s true that the use of Section 4’s involuntary-removal mechanism for the first time in American history—especially for a President who is not ill and who still has public support—could trigger a political crisis,” Rosen said. Citing arguments made back in 1965, Rosen said it was clear the amendment was written to be vague on this point and left open the possibility of presidential disability as ‘a political decision, left to the vice president, the Cabinet, and ultimately Congress.’”

“If, at some point in the future, those officers decide it is more politically advantageous for the Republican Party to remove Trump under the Twenty-fifth Amendment than to allow him to be impeached for obstruction of justice, nothing in the text or original understanding of the Amendment would prevent them from doing so,” Rosen concluded.

Also, Congress has the power to impeach a President, which would require a two-thirds vote in the Senate for conviction after a House majority votes in favor of an impeachment trial. Under the 25th Amendment, as Kalt and Pozen pointed out, both the House and the Senate would need to agree by a two-thirds vote that the President is unable to serve – a higher standard to be met than the impeachment process.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.