As the presidential campaign heads towards its conclusion, lawyers for at least one candidate have threatened a defamation lawsuit against a major newspaper. So how can a candidate for president sue if she or he is a public figure?

In this instance, Donald Trump’s attorneys are warning the New York Times that they may sue for defamation on his behalf after the Times reported on two women who made sexual harassment allegations against Trump. The newspaper’s editor said the reporting fell in the realm of public service journalism.

To be sure, candidates can always file a lawsuit, but to succeed in court, the candidate would need to meet a high standard of defamation based on a landmark Supreme Court decision.

Defamation is a legal concept related to the First Amendment, but state laws generally define its elements. Lawyers for a public figure such as Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump would need to prove false statements were knowingly published, with malice, or with a reckless disregard for their accuracy. That “actual malice” test goes back to the Supreme Court’s New York Times v. Sullivan decision in March 1964.

“A State cannot, under the First and Fourteenth Amendments, award damages to a public official for defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves ‘actual malice’ - that the statement was made with knowledge of its falsity or with reckless disregard of whether it was true or false,” said Justice William Brennan in his majority opinion.

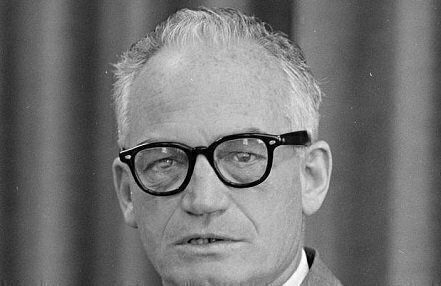

Later in 1964, the actual malice rule would see its first test in a presidential campaign. In its October/November 1964 issue, Fact magazine published a special report on the fitness of Republican candidate Barry Goldwater to hold the office of president. The magazine said that Goldwater has a “severely paranoid personality and was psychologically unfit for the high office to which he aspired,” a conclusion it reached after polling a group of psychiatrists. Fact’s editor also wrote a story how he believed Goldwater was unfit for office based on his own observations of Goldwater’s mental health.

After the 1964 election (which he lost), Goldwater sued the magazine and its editor, Ralph Ginzburg, for $1 million in compensatory damages and $1 million in punitive damages. A jury awarded Goldwater $1 in compensatory damages and $75,000 in punitive damages. The case wound up in appeals for several years.

In 1969, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the lower-court decision in Goldwater v. Ginzburg. The appeals court said that “by seeking election to the office of President of the United States, Senator Goldwater invited the press and the public to scrutinize every aspect of his life, public and private alike.” But it agreed with the lower court that Fact magazine had met the test for knowingly making false statements with malice.

“A full appreciation of the tone and tenor of the articles in the ‘Goldwater issue’ can only be had by reading the full text of the two articles,” it said. “False statements are protected only if they are honestly made. … The use of calculated falsehood, however, would put a different cast on the constitutional question.”

The appeals court said Goldwater was entitled to damages under a decision that came after the New York Times v. Sullivan decision, the 1967 Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts case. “If nominal damages are awarded, the offending book, magazine, or newspaper publisher may not then avoid any additional liability, which a libeler in a different occupation normally might incur, by claiming a special status or an entitlement to special protections under the First Amendment,” the appeals court said, citing the Curtis decision. “The book, magazine or newspaper publisher who with actual malice prints defamatory falsehoods about a public official or public figure has put himself beyond the pale of the First Amendment.”

In March 1970, the Supreme Court decided not to take the case on appeal, but Justice Hugo Black did attach a dissent to the Court’s denial. “I cannot subscribe to the result the Court reaches today because I firmly believe that the First Amendment guarantees to each person in this country the unconditional right to print what he pleases about public affairs,” Black wrote.

Black cited Goldwater’s unique status as a presidential candidate. “The public has an unqualified right to have the character and fitness of anyone who aspires to the presidency held up for the closest scrutiny. Extravagant, reckless statements and even claims which may not be true seem to me an inevitable and perhaps essential part of the process by which the voting public informs itself of the qualities of a man who would be president,” Black wrote.

“The decisions of the District Court and the Court of Appeals in this case can only have the effect of dampening political debate by making fearful and timid those who should under our Constitution feel totally free openly to criticize presidential candidates,” he concluded.

As for Trump’s case, it remains to be seen if there is a future lawsuit against the Times. But earlier this year, the candidate made it clear that he doesn’t agree with the current protections offered to publishers in their reporting about public figures.

“I'm going to open up our libel laws so when they write purposely negative and horrible and false articles, we can sue them and win lots of money. We're going to open up those libel laws,” Trump said at February rally in Texas. “So when The New York Times writes a hit piece which is a total disgrace or when The Washington Post, which is there for other reasons, writes a hit piece, we can sue them and win money instead of having no chance of winning because they're totally protected," Trump said.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.