On March 28, 1834, the U.S. Senate censured President Andrew Jackson in a tug-of-war that had questionable constitutional roots but important political overtones.

Congressional censure motions against a sitting President have always been controversial. In addition to Jackson, John Tyler and James Polk faced censure resolutions. Abraham Lincoln faced a censure problem during the Civil War, which was ironic, since Representative Lincoln led the censure movement against President Polk.

In modern years, censure motions were introduced against Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton, but not pursued.

Censure motions are subject to votes in either the House of Representatives or the Senate, and their sharply worded language is essentially a public shaming of government officials.

The most-famous censure motion in congressional history happened in 1954, when the Senate passed a censure motion against Joseph McCarthy, who was a key figure in the post-World War II Communist Red Scare era.

The motion said that McCarthy “acted contrary to senatorial ethics and tended to bring the Senate into dishonor and disrepute, to obstruct the constitutional processes of the Senate, and to impair its dignity; and such conduct is hereby condemned.”

The effective punishment came against McCarthy in a separate motion, where he lost a key committee chairmanship.

The constitutional precedent for the censure motion comes from Article 1, Section 5, Clause 2, which says that “each House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings, punish its Members for disorderly behavior, and, with the Concurrence of two thirds, expel a Member.”

However, there is nothing in the Constitution about Congress having the ability to pass a censure motion against a member of another branch of the government. And the word “censure” doesn’t appear in the Constitution.

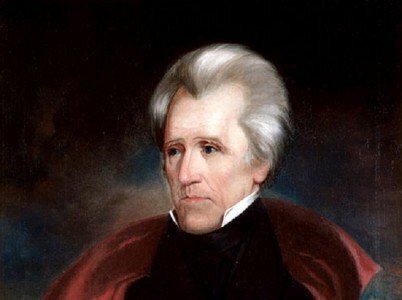

These facts weren’t lost on President Andrew Jackson in 1834 when he faced the first-ever censure motion against a sitting President. Jackson was locked in a fierce battle against Henry Clay and the Whigs over the Second Bank of the United States.

In 1832, Jackson vetoed a congressional move to re-charter the bank; the Whig-controlled Senate and Clay asked Jackson to supply notes from his Cabinet meeting about the veto decision and Jackson refused to supply the documents. Clay then led the censure motion, which passed by a 26-20 vote.

“Resolved, That the President, in the late Executive proceedings in relation to the public revenue, has assumed upon himself authority and power not conferred by the Constitution and laws, but in derogation of both,” the motion read.

Jackson’s response was quite longer.

“I thus find myself charged on the records of the Senate, and in a form hitherto unknown in our history, with the high crime of violating the laws and Constitution of my country,” he wrote in a letter to the Senate.

“The resolution of the Senate is wholly unauthorized by the Constitution, and in derogation of its entire spirit. It assumes that a single branch of the legislative department may for the purposes of a public censure, and without any view to legislation or impeachment, take up, consider, and decide upon the official acts of the Executive. But in no part of the Constitution is the President subjected to any such responsibility, and in no part of that instrument is any such power conferred on either branch of the Legislature,” Jackson added.

Jackson remained angry about censure resolution for years and his supporters had the motion expunged from the Senate records in 1837 when the Democrats controlled the chamber.

“The Senate is no longer a place for any decent man,” Clay said after the censure motion was expunged.