Constitution Daily is hosting a blog symposium honoring the 50th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act. Contributions come from Roger Clegg, Rick Hasen, Kermit Roosevelt, J. Christian Adams, Brianne Gorod, Nathaniel Persily and Rick Valelly.

Fifty years ago today, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Voting Rights Act of 1965, taking an enormous step toward protecting the right to vote for all Americans.

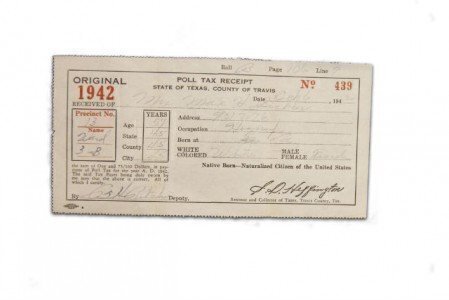

Decades of concerted effort on the part of state and local officials to disenfranchise African Americans through the use of poll taxes, literacy tests and sheer intimidation had inspired little action from Congress.

But the momentum created by the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as well as the horrified reaction to violence inflicted upon voting-rights protesters marching from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in March 1965, drove federal legislators to craft a response.

The resulting legislation, signed into law at the Capitol with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks and other civil-rights leaders looking on, has stood firmly for nearly half a century.

Among other measures, the VRA outlawed literacy tests and empowered the U.S. Department of Justice to challenge the use of poll taxes in state and local elections. Passage of the 24th Amendment in 1964 already barred the use of poll taxes in national elections.

Section 2 is largely a restatement of the 15th Amendment, prohibiting any voting rules or procedures that discriminate on the basis of race or color. Amendments to the VRA in 1975 extended its protections to members of a language minority group, such as speakers of Spanish or Native American languages.

Moreover, thanks to another round of amendments in 1982, citizens today who challenge voting regulations under Section 2 need only prove that, in the “totality of the circumstance of the local electoral process,” the rules have the effect of abridging the right to vote.

In crafting the original VRA, Congress also provided for special intervention in jurisdictions where racial discrimination is believed to be greatest. Under Section 5, those parts of the country identified by a formula established in Section 4 must obtain “pre-clearance” from the DOJ or the U.S. District Court of the District of Columbia before making any changes to its voting laws.

In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), however, the Supreme Court struck down the Section 4 formula, leaving Section 5 intact but requiring legislators to redraw its coverage before further enforcement. Since the ruling, several amendments have been proposed but Congress has thus far declined to act.

Addressing the House and Senate just over a week after “Bloody Sunday,” President Johnson summoned the two chambers to action.

“Our fathers believed that if this noble view of the rights of man was to flourish, it must be rooted in democracy,” he boomed. “The most basic right of all was the right to choose your own leaders. The history of this country, in large measure, is the history of the expansion of that right to all of our people.”

“Many of the issues of civil rights are very complex and most difficult,” Johnson went on. “But about this there can and should be no argument. Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote. There is no reason which can excuse the denial of that right. There is no duty which weighs more heavily on us than the duty we have to ensure that right.”

Now, 50 years after that landmark speech and 51 years after Freedom Summer, the nation may well be in the midst of a second "Courtroom Summer." Voting rights litigation is ongoing in North Carolina, as well as in Ohio and Wisconsin, where two other voting lawsuits ended only recently. And just yesterday, a federal appeals court ruled on a big case from Texas.

In the coming months and years, the fate of the VRA will be sorted out in Congress and in the courts. But its legacy as the singular triumph of the civil rights movement will remain strong.

Nicandro Iannacci is a web strategist at the National Constitution Center.