In a special Halloween feature, Constitution Daily looks at two real-life body snatching stories related to three U.S. Presidents, and a ghoulish tale involving Alexander Hamilton and John Jay.

Grave robbing seems horrendous today, but it was big business for two centuries in America, when bodies were dug up from graves or taken from vaults to be sold to medical facilities as study aides.

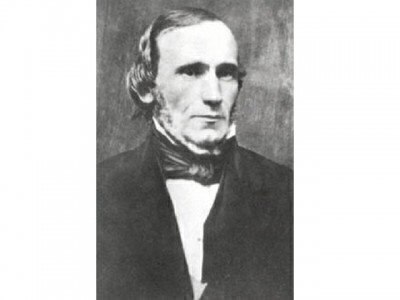

No one was spared from the body snatchers, including the son of President William Henry Harrison, who was also the father of President Benjamin Harrison.

The era after the Civil War was especially booming for people who stole bodies and then sold them under clandestine circumstances to medical schools. Known as “resurrectionists,” professional body snatchers were part of a national network where bodies were stolen from graves, transported, stored, and sold to medical schools. Body snatchers were careful to just take the bodies, and not objects, from graves, in order to take advantage of a legal technicality that would exempt them from felony charges.

But it was the theft of the body of John Scott Harrison in Ohio in 1878 that sparked public outrage over the practice.

Harrison, himself a former U.S. congressman, passed away at the age of 73. When his family proceeded to a cemetery in North Bend, Ohio, to bury Harrison, they discovered that the grave of Harrison’s recently deceased nephew, Augustus Devin, had been robbed, and the body was missing.

Harrison’s sons protected the burial site for the former congressman by placing large stones on top of the crypt, and one son, John Harrison, headed to Cincinnati to find Devin’s body, accompanied by another cousin and a constable.

There were suspicions that Devin’s body could be at the Medical College of Ohio. After interrogating a janitor, John Harrison spotted a pulley with a rope, and when the rope was tugged, there was a heavy weight on the end.

Harrison pulled up the body, possibly expecting to find Augustus Devin. Instead, a shroud was removed and the body of Congressman John Scott Harrison was at the end of the rope. The body snatchers had drilled through the casket and transported the body to the school in less than 24 hours.

Two men were later arrested in the case, including the janitor, and Devin’s body was found in Michigan, where it had been sent to another school. The Harrisons had hoped to keep the incident out of the newspapers, but it quickly became public, and a large crowd gathered when Devin’s body was re-interred.

Public outrage over body snatching and medical schools wasn’t new in 1878. In fact, 100 years earlier, a riot occurred in New York City that involved two Founding Fathers, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay.

The April 1788 Doctors’ Riots in New York purportedly started after a local man discovered that his recently deceased wife’s body parts were being used at a nearby medical facility. Hamilton and Jay were among the public officials that tried to appease a mob. The crowd responded by tossing rocks at the men, and Jay was knocked unconscious.

In 1876, there was the well-publicized tale of grave robbers who targeted the corpse of President Abraham Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois.

A counterfeit ring had fallen on hard times and plotted to steal Lincoln’s body and sell it back to the government. The ring’s leader, Big Jim Kennally, had bragged about the plot, and one of his recruits was a man named Lewis Swegles, who was known as a professional body snatcher.

When Kennally’s gang approached Lincoln’s unguarded grave, the plot seemed assured. But Swegles turned out to be a Secret Service agent. The men fled when another agent’s weapon went off prematurely, but they were caught within days.

Ironically, one of Lincoln’s last acts as president was to approve the creation of the Secret Service. He signed the law on April 14, 1865, just hours before he was shot at Ford’s Theatre in Washington.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.