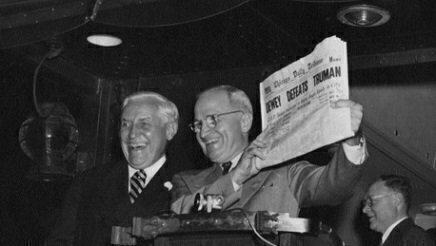

In the legacy of presidential history, Harry Truman may be best remembered by one photograph. So how did the 33rd president wind up holding a newspaper that showed him losing an election he had already won?

On Wednesday, November 3, 1948, the Chicago Tribune published the most famous political headline in U.S. history, proclaiming Thomas Dewey as the next President after Tuesday's election. In fact, Truman was the winner, not Dewey.

Earlier in 1948, Truman was running for his first elected term in the White House. A vice president, the little-known Truman replaced Franklin Roosevelt after FDR passed away in April 1945 just after the start of his fourth presidential term.

Earlier in 1948, Truman was running for his first elected term in the White House. A vice president, the little-known Truman replaced Franklin Roosevelt after FDR passed away in April 1945 just after the start of his fourth presidential term.

His presidency was anything but ordinary, and the Democrats had been in the White House for almost 16 years as Truman approached Election Day on November 2, 1948 and a formidable Republican candidate, Thomas Dewey.

Truman was also running against a Democrat faction called the Dixiecrats, who opposed Truman’s efforts to integrate the military. The Dixiecrats, led by Strom Thurmond, took 39 electoral votes in the 1948 election to weaken the former “Solid South” controlled by Roosevelt’s Democratic Party. And another former Roosevelt vice president, Henry Wallace, ran on the Progressive Party ticket.

And then there was the polling data. Dewey’s victory was so expected that the Roper poll had stopped doing surveys in September about the race. The Gallup poll had the race at 45 percent for Dewey and 41 percent for Truman in October.

So the night of November 2, the editors of the Chicago Tribune, based on the advice of their Washington editor and a need for an early first edition, approved a gigantic headline that read, “Dewey Beats Truman.”

The Tribune also apparently based its decision on a recent Life magazine cover that called the election for Dewey and a general low regard for Truman, whom it had called a “nincompoop” on its editorial pages. (Only an estimated 15 percent of newspapers nationally supported Truman in the election.)

But when the dust settled, Truman easily defeated Dewey in the Electoral College, by a 303 to 189 margin. Truman also won by a 50-45 percent popular vote.

What the newspapers and pollsters didn’t understand was Truman’s background as a fighter, and the tendency for voters to wait until closer to Election Day to pick a candidate.

Earlier in his political career, Truman had been written off in the 1940 U.S. Senate election. When Truman’s political ally, Tom Pendergrast, was convicted of tax evasion in 1939, few people thought Truman stood a chance of getting re-elected in Missouri. Truman hit the campaign trail hard, spoke about his war record and experience as a common man, and pulled off an upset.

At a raucous 1948 Democratic convention in Philadelphia, Truman made it clear that he would add a campaign against Congress to his set of tactics.

“Congress has still done nothing,” Truman pleaded at the deeply divided convention. “With the help of God and the wholehearted push which you can put behind this campaign, we can save this country from a continuation of the 80th Congress, and from misrule from now on.”

Truman survived a walkout by the Dixiecrat faction of the Democrats at the convention and successfully used the “do-nothing” Congress as a weapon against the favored Republican candidate, Dewey.

Truman also hit the campaign trail hard after Labor Day, using a presidential train to cross the country making more than 200 campaign speeches. Dewey was known as a dull speaker and campaigned far less. The pollsters also stopped polling before the effect of Truman’s whistle-stop campaigning took hold.

Late on November 2, Truman went to sleep in Independence, Missouri, knowing he led by one million votes in early results but was expected to lose. Four hours later, he received a call from the Secret Service – Truman was leading in the election and expected to win.

Dewey conceded the next day, but the famous Tribune photograph was taken two days later, as the Truman family was in Saint Louis and returning to Washington. Life photographer W. Eugene Smith caught Truman in the moment after a staffer handed the President a copy of the Tribune early edition that had been found on a train earlier.

The rest was history, and perhaps the most famous photograph in American politics.