Lyle Denniston, Constitution Daily's Supreme Court correspondent, looks at a legal challenge at the Supreme Court about a 1990s law that determines how copyright-protected music is used on YouTube and other Internet websites.

Throughout the history of the Constitution, America has been carrying on a kind of a thought experiment. It goes like this: if creative forms of writing and speaking are monopolized by their creator, does that stifle the ability of others to add to, or modify, that expression in their own way? Constitutionally speaking, does copyright protection run counter to First Amendment rights?

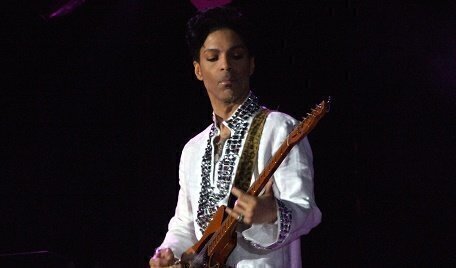

The Supreme Court is now being asked to step right into the middle of this cultural controversy in a Digital Age setting. It arises in the mundane context of a mother who posted on YouTube a 29-second home video of her little boy bouncing rhythmically to a celebrated – and copyright-protected – song by the late performing artist, Prince. The song is titled “Let’s Go Crazy.” The video has been viewed more than a million times.

The legal controversy that is now known popularly as the “dancing baby case” has reached the Supreme Court in dueling appeals by that Pennsylvania mother, Stephanie Lenz, and the giant music publishing entity, Universal Music Corp., which is the guardian of copyright of Prince’s music. From the robust debate in the legal papers already filed in the case, it is clear that this has the potential to turn into a controversy that will go well beyond the facts of this particular episode.

The Justices are scheduled to consider those appeals this week – at least to decide whether to hear them. Both sides are pressing their view that the issues are of major importance both to holders of copyrights and to people who post billions of items to the websites of Internet platforms like YouTube, Facebook and Twitter, among many others.

At the center of the case is a 1998 law – the Digital Millennium Copyright Act -- that Congress passed in an attempt to strike a balance between the intellectual property rights of copyright holders and the free-speech rights of Internet users (and, in the balance, to create a zone of legal safety for Internet sites that host material composed and posted by others).

The mechanisms that the Act created are called the “take-down” and “put-back” procedures. The first gives holders of copyrights the option to demand that a site remove or disable access to a posted item that the holders believe infringes their property rights. The latter entitles the person who did the post to a notice of the “take-down” and the option to demand that it be put back up on the site, arguing that it does not violate copyright. If the service provider quickly takes down and puts back up the post in response to such demands, it is itself protected from a claim that it contributed to copyright violation.

Copyright holders, in sending a take-down notice, must declare a “good faith belief” that the posted item did violate copyright, and the composers of the posts must declare, in sending a put-back demand, their own belief that the post did not infringe on copyright. If either side has been found to have misrepresented the required declaration, that violates the law. Penalties can be money damages and a duty to pay the other side’s attorneys’ fees and costs.

As the “dancing baby case” reached the Supreme Court, the two sides approach it from very different perspectives.

The lawyers for Stephanie Lenz are arguing that a federal appeals court made it much easier for Universal Music – and other copyright holders – to censor expression on the Internet by claiming that copyright has been violated, when they have not really examined closely whether the posted item may have been put up legally as – for example -- a form of “fair use” of the copyrighted item. The appeals court, that filing complains, only required a simple statement of belief without evidence to support it.

Universal Music’s lawyers are arguing that Lenz should never have been allowed to pursue her lawsuit claiming that Universal violated the 1998 law, because she cannot show that she actually suffered any injury personally. It should not be enough, that appeal contends, that the law was violated. That, it asserts, is insufficient to show “standing to sue” under the Constitution’s Article III.

The appeals court that spared Universal Music some of the burden of proving its belief that there was a copyright violation, also ruled that, even though the only harm to Lenz was that she was the victim of a violation of the law, that could be enough to justify at least a modest damage award – perhaps as little as $1 as a demonstration of illegality.

On Lenz’s side of the case, major corporations that operate popular platforms that host content posted by others are arguing that there is rampant abuse of the “take-down” process under the 1998 law, and the result is to smother the free-speech potential of the digital medium. They join Lenz in arguing that the appeals court decision at issue has virtually destroyed the legal concept that a “fair use” of copyrighted material is not illegal.

Universal Music has the fervent support of a powerful lobbying group for the music industry, the trade association Recording Industry of America. Over the years, it has made a reputation as a most energetic defender of the rights of composers and as a fervent foe of easy modes of downloading music by digital consumers. The group’s lawyers are urging the court to block lawsuits like the one Lenz has filed, and among its arguments is that there are “billions of downloads” of copyrighted music via the Internet. Their legal brief adds that “new systems are always evolving, often armed with ingenious technologies to thwart copyright enforcement.”

How the Justices will react to the two new appeals is uncertain. There does not appear to be a split among lower courts on what a copyright holder must do to prove it fears that an Internet post infringes on a copyright, so the Justices may want to let that percolate in the lower courts for some period of time before getting directly involved. The issue that Universal Music is raising – how to satisfy the right to sue under Article III – is, however, a frequent one before the Justices, and there is a precedent on that point (one that limits the concept of “standing”) that is only a few months old.

The Justices’ initial reaction may be known within a few days.

Legendary journalist Lyle Denniston is Constitution Daily’s Supreme Court correspondent. Denniston has written for us as a contributor since June 2011. Denniston has covered the Supreme Court since 1958. His work also appears on lyldenlawnews.com.