National Constitution Center constitutional literacy adviser Lyle Denniston was at the Supreme Court on Wednesday, where all signs pointed to a possible even split between the eight Justices on the latest Obamacare challenge - an outcome that may have seemed surprising several years ago. Six years to the day after President Obama signed into law his most ambitious domestic policy, the Affordable Care Act, the Supreme Court on Wednesday cast into deep doubt one of its most important features. With only eight justices on the court at this point, a packed courtroom waited eagerly for signs that a majority might emerge, one way or the other, on the legality of the requirement that non-profit employers provide birth-control devices and services to women of child-bearing age, at no cost to the women.

Six years to the day after President Obama signed into law his most ambitious domestic policy, the Affordable Care Act, the Supreme Court on Wednesday cast into deep doubt one of its most important features. With only eight justices on the court at this point, a packed courtroom waited eagerly for signs that a majority might emerge, one way or the other, on the legality of the requirement that non-profit employers provide birth-control devices and services to women of child-bearing age, at no cost to the women.

In a vivid illustration of the problem that the court might face while it awaits a replacement for the late Justice Antonin Scalia, all indications at a 94-minute hearing were that the court might not have any dependable way to avoid splitting 4-to-4 on the contraceptive mandate – essentially, a non-result, setting no precedent.

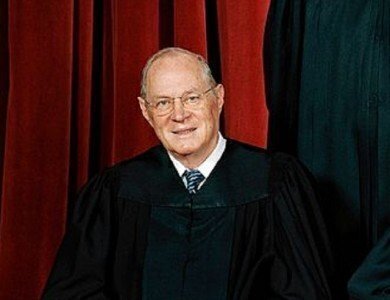

Simply put, that prospect was something of a surprise. Less than two years ago, in the court’s first ruling on the birth-control mandate (applying then to profit-making corporations), Justice Anthony M. Kenney had written a separate opinion that embraced the very compromise approach that was being challenged on Wednesday by non-profit religious institutions. That approach was that women would get access to free pregnancy-prevention methods but the religious institutions where those women worked would not have to supply them if that ran counter to the institutions’ beliefs.

Instead, women would get those from their employers’ insurance companies without involving directly the religious employer. That was a compromise that the court’s majority had seemed to endorse in 2014.

As this controversy has unfolded since then, the religious employers at non-profit hospitals, colleges and charities have taken their turn to go to the Supreme Court with an argument that their religious rights would actually be violated, after all. The health care plans through which contraceptive devices and methods would be channeled to their female workers or college students, their lawyers argued, were those institutions’ own plans, and their religious sponsors would thus be a partner in supplying the contraceptives to which they fervently object on religious grounds.

The government, they insisted, would have to find another approach, without their involvement in any way, to providing the birth-control devices and techniques that the government believed women wanted to have but might not buy on their own.

The first lawyer to rise in the court on Wednesday to make those arguments, Washington, D.C., attorney Paul D. Clement, contended that the government was attempting to turn the nonprofit institutions into “conscientious collaborators” with it. The government, he said, was trying to “hijack” the non-profits’ own health care plans, making them a part of the process of supplying contraceptives in direct violation of their religious tenets.

Resistance also came from another Washington lawyer speaking for other religious nonprofits, Noel Francisco. Those two attorneys’ pleas were then countered by an argument from the Obama administration’s top lawyer in the Supreme Court, U.S. Solicitor General Donald B. Verrilli, Jr.

While the non-profit institutions’ lawyers took turns at the lectern, the court’s four more liberal Justices dominated the hearing, leaving almost no doubt that they were mainly on the administration’s side. If it were up to them, it seemed clear, the mandate would survive; they appeared inclined to accept that Congress had done enough to shift access to the birth-control devices and methods away from objecting religious employers and to insurance companies.

As the argument unfolded, the large audience focused its attention on Justice Kennedy. But Kennedy soon began creating an impression that his views had changed, perhaps in significant ways, since the contraceptives provisions had first gone before the court in 2014.

Kennedy had been involved only intermittently on Wednesday as the two lawyers for the religious entities were arguing, and gave little hint of what he was thinking, beyond suggesting that he was not inclined to treat universities the same as other religious employers in deciding how complete an exemption they could be given from a government program such as the contraceptives mandate.

But, as soon as the government lawyer, Solicitor General Verrilli, had opened his argument, Kennedy appeared to be troubled at what he took to be a refusal to give religious entities a complete opt-out from the contraceptives mandate. In tone if not entirely in substance, he sounded as if he expected the government to go further to accommodate a religious objection, and perhaps should have to do more to keep a faith organization out of even a sidelines involvement with access to contraceptives.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., soon got involved in the argument mainly to suggest that he agreed with attorney Clement that the government was seeking to “hijack” the existing health insurance plans of religious entities like those created and maintained by the Little Sisters of the Poor.

Justice Kennedy soon stepped back into the rapid-fire exchanges with the Solicitor General, suggesting that the government lawyer was dismissing the religious entities’ concerns about being implicit in sinful conduct toward their employees. There was a distinct sound of sarcasm in Kennedy’s voice at that point, almost as if he were mocking the government’s argument.

After a series of tense exchanges between the government lawyer, the Chief Justice and Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr., Justice Kennedy got involved again to suggest that the church-run benefit plans involved in the case “are, in effect, subsidizing the conduct that they deemed immoral.” By that point in the argument, it was becoming plainer that Kennedy had become notably more skeptical than he had been in the first examination of the mandate, and was now more closely aligned in opposition to the birth-control provisions with the Chief Justice and Justice Alito.

With Justice Clarence Thomas saying nothing during the hearing, it could be assumed he retained the opposition he had joined in expressing when the mandate was before the court in the context of for-profit businesses.

If the indications at the Wednesday hearing held as the court moved forward to vote on the case (the initial vote will be at a private conference this Friday), there appeared to be strong indications that the Justices might split 4-to-4. That would leave the lower courts divided on the issue, with no final resolution by the court – perhaps until a ninth Justice had become a member.