Arguing that one of President Trump’s Cabinet secretaries should not have to answer lawyers’ questions about why he plans to ask everyone in America about their citizenship as part of the 2020 census, the Administration urged the Supreme Court on Monday to delay a trial on that issue, now set to start next Monday.

Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross should be spared from questioning about his “mental processes” as he made plans for the next census, Administration lawyers argued in emergency papers filed at the Supreme Court. By getting their filing in by an afternoon deadline set by the Court a week ago, the Trump legal team keeps in effect a temporary order by the Justices barring direct questioning of Ross.

Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross should be spared from questioning about his “mental processes” as he made plans for the next census, Administration lawyers argued in emergency papers filed at the Supreme Court. By getting their filing in by an afternoon deadline set by the Court a week ago, the Trump legal team keeps in effect a temporary order by the Justices barring direct questioning of Ross.

That temporary order, however, did not delay the start of the trial on November 5. The new filings sought postponement of that, too, until the Justices decide the government’s new appeal on the census issue.

Although the controversy centers on the questioning before and at the trial of key government officials, the dispute raises major constitutional questions about the power of the courts to inquire into how government policy is made at the highest levels, and about how the federal census is supposed to be taken every decade.

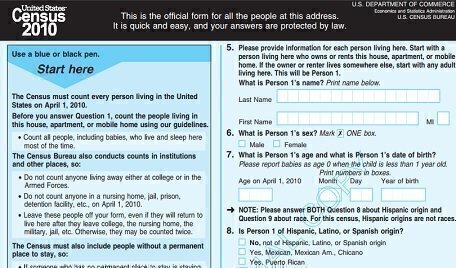

A group of state and local governments is contending in a major lawsuit in New York City that Commerce Secretary Ross – whose department includes the Census Bureau — wants to press the citizenship question with the aim of reducing the census count of racial minorities, especially those of Latin heritage. Similar lawsuits are pending in California and Maryland, but trials in those cases are not set to occur until January.

The New York lawsuit argues that Ross has shielded a discriminatory motive by giving false explanations of why the question would be added in questionnaires going to every U.S. household. It also argues that Ross was under pressure from White House aides – including former advisers Steve Bannon and Kris Kobach – to add that question. Kobach, a state official in Kansas as well as a former adviser to President Trump, has long pressed the issue of citizenship in voting, contending that non-citizens often seek to cast ballots illegally.

The Constitution itself requires that every ten years there be an actual count of the U.S. population. The count is supposed to include all people, not just those who are citizens. Thus, foreign-born individuals living in the U.S. without legal permission are counted, too.

The census totals are used to determine how many seats each state is to have in the U.S. House of Representatives, and also are the basis for the allocation of vast sums of money in federal government programs.

If the citizenship question is posed, the lawsuit has asserted, it will reduce the actual count because households where undocumented immigrants may be living will refuse to give full responses. As a result, the states and localities that are suing will be harmed directly by the under-count, they say.

A week ago, the Supreme Court temporarily barred a questioning session with Ross, but that order was temporary, in effect until the Administration formally appealed a trial judge’s order requiring that and similar questioning of other high-level government officials. With Monday’s filing, the deposition of Ross remains on hold, but not those of other officials. In fact, some sessions with other officials have already occurred.

The trial judge, District Court Judge Jesse M. Furman, ordered those sessions after finding that Secretary Ross had acted in “bad faith” in discussing his reasons for adding the citizenship inquiry. The jurist said that would be necessary in order to probe the legality of Ross’s decision, under federal law and under the Constitution’s ban on racial discrimination.

When the Supreme Court acted a week ago to delay the deposition of Ross, Justices Neil M. Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas argued in a separate opinion that the Court should have gone further, and shut down the trial altogether until the dispute over government officials’ testimony is resolved by the Justices. The Administration’s lawyers, in the new documents, relied heavily upon the opinion of those two Justices.

It is nearly unprecedented, the new filing contended, for high-level government officials to be forced personally to give testimony in lawsuits challenging federal action or programs. It threatens the performance of those officials’ regular duties and thus threatens to violate the Constitution’s separation of powers between the courts and the other branches of the government.

The Administration is now seeking these actions by the Justices:

First, an immediate order stopping all proceedings in Judge Furman’s court, until the Justices take the next steps sought by the government.

Second, a prompt order delaying the trial completely, until the Justices resolve in a final way the dispute over officials’ testimony.

Third, a formal order directly commanding Judge Furman not to require any questioning of government officials, and instead to decide the legality of the citizenship question solely on the basis of records of how the Commerce Secretary and Census Bureau officials analyzed whether to ask that question during the census enumeration. The new government filing said that 150,000 pages of documents have already been supplied for that review.

Fourth, as an alternative to that direct order to Judge Furman, an order by the Justices agreeing to review a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit refusing to limit the trial judge’s management of the case.

Finally, the government asked that the entire dispute be handled by the Justices on an expedited schedule, since the Census Bureau has only a limited amount of time remaining to prepare the plans for the actual taking of the census.

Because of the dispute that has arisen over direct questioning of key officials, Judge Furman has said that he will conduct the trial on two levels: considering only the documents so far submitted by federal agencies, and separately considering what officials say under questioning before and during the trial. If the Supreme Court ultimately bars the second kind of review, the judge said, the decision will then rest only on the documents on file in his court.

That split-level process simply will not work, the Administration argued in its Monday filings. The Court is expected to act swiftly on at least some of the government’s requests.