On May 12, 1977, the Supreme Court set a precedent about union dues and public-worker unions that could be overturned in the next few weeks.

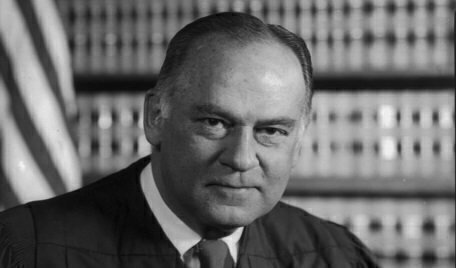

In a unanimous opinion from the Court in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, Justice Potter Stewart said that public-sector workers could be compelled to "support legitimate, non-ideological, union activities germane to collective-bargaining representation.” The Abood Court said that a state could balance managing its employees and labor interests to avoid “free rider” situations where non-union workers benefited from a union’s advocacy for pay raises and other benefits without paying for the negotiation process.

In a unanimous opinion from the Court in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, Justice Potter Stewart said that public-sector workers could be compelled to "support legitimate, non-ideological, union activities germane to collective-bargaining representation.” The Abood Court said that a state could balance managing its employees and labor interests to avoid “free rider” situations where non-union workers benefited from a union’s advocacy for pay raises and other benefits without paying for the negotiation process.

Stewart and the Court realized this balancing act could cause some First Amendment problems. “To be required to help finance the union as a collective bargaining agent might well be thought, therefore, to interfere in some way with an employee's freedom to associate for the advancement of ideas, or to refrain from doing so, as he sees fit,” Stewart said. “But the judgment clearly made in Hanson and Street is that such interference as exists is constitutionally justified by the legislative assessment of the important contribution of the union shop to the system of labor relations established by Congress.”

To address First Amendment interests, the Court made sure that non-member contributions to a public-sector union were meant for the true costs of representation and not for advocating political causes.

Since the Abood decision, three challenges had arrived at the Court in recent years seeking to overturn the decision or seriously amend it. In 2015 in Harris v. Quinn the Court said home health care aides in Illinois didn’t have to pay union representation costs for a public workers’ union they didn’t belong to. But the Court also said the workers weren’t “full-fledged public employees,” upholding in principle the Abood decision.

Then in 2016, the Court was asked in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association to decide if requiring public school teachers to pay mandatory dues for union activities violated the First Amendment. After the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, a 4-4 court couldn’t decide the case and sent it back to lower courts, leaving in place the precedent that teachers and other public workers, in about half of the nation’s unions, had to pay fees to support unions, even if they don’t participate in them.

The current case at the Court is Janus v. AFSCME, where nine Justices, including Neil Gorsuch, heard arguments in February in a similar case about the Illinois Public Labor Relations Act, which requires all employees working at a public agency or public organization to pay a fee for unions to negotiate contracts, even if some employees don’t belong to unions.

Since Gorsuch joined the bench to replace Scalia, court observers have believed Gorsuch would cast the deciding vote when the Abood case was challenged in court again. But Gorsuch didn’t ask any questions during the Janus case’s arguments this February.

To union officials, any decision overturning Abood is seen as a direct threat to the existence of public unions. Abood’s opponents view it as an unconstitutional restraint on free speech and association. In any event, a Supreme Court decision that could potentially overturn a 41-year-old precedent would be significant and garner a lot of attention outside of normal Supreme Court coverage.

The Court’s decision in the Janus case is expected by late June.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.