How do Presidents deal with sensitive information requests from Congress? Sometimes they just say No, citing a right of executive privilege that doesn’t technically exist in the Constitution. But just because the words “executive privilege” aren’t directly written in our founding document, doesn’t mean the courts will refuse to recognize it as a legitimate right or power held by the President.

Currently, the Trump administration has requested that a federal district court based in Detroit consider an executive privilege claim related to memos prepared by Trump campaign adviser Rudy Giuliani about an alleged Muslim ban – written before Trump became President. The request is under consideration.

Currently, the Trump administration has requested that a federal district court based in Detroit consider an executive privilege claim related to memos prepared by Trump campaign adviser Rudy Giuliani about an alleged Muslim ban – written before Trump became President. The request is under consideration.

There also have been reports that the Trump administration could invoke executive privilege to block former FBI director James Comey from testifying before the Senate. A presidential spokesperson on Friday wouldn’t confirm or deny such an action was possible.

Related Story: The House’s contempt powers explained

The debate over the President’s ability to ignore or at least loudly complain about these congressional requests dates back to incidents involving George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, and Aaron Burr. However, it took the Supreme Court to establish the official concept of executive privilege in the Watergate Tapes decision, United States v. Nixon, in 1974.

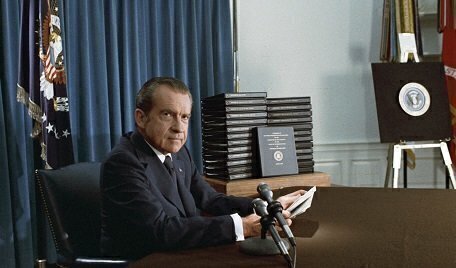

Chief Justice Warren Burger issued the unanimous opinion with input from seven other Justices in July 1974. President Richard Nixon sought to block Watergate special prosecutor Leon Jaworski from getting access to unedited tapes of conversations made inside the White House. The recordings were believed to indicate a cover-up initiated by Nixon; instead, Nixon had supplied edited transcripts of the conversations and claimed executive privilege.

Nixon’s attorneys argued the President was entitled to the absolute privilege of confidentiality for all his communications under various interpretations of the Constitution, and that the separation of powers doctrine blocked him from honoring a judicial subpoena in an ongoing criminal prosecution.

The Burger Court’s opinion recognized the right of executive privilege, but it also said executive privilege did not apply in Nixon’s case. Chief Justice Burger’s decision went back to the seminal case of United States v. Burr in 1807 to explain its reasoning. In the Aaron Burr treason trial, Chief Justice John Marshall, sitting on a circuit court, ruled that a subpoena could be issued to President Thomas Jefferson to produce documents.

Burger agreed with Marshall’s argument that an information request to a President from a court was a special case. “We agree with Mr. Chief Justice Marshall's observation, therefore, that ‘in no case of this kind would a court be required to proceed against the president as against an ordinary individual,’” Burger said.

But the concept of executive privilege was not absolute. Again, the Burger decision quoted Chief Justice Marshall in his role as a judge in the Burr treason trial. “Marshall's statement cannot be read to mean in any sense that a President is above the law, but relates to the singularly unique role under Art. II of a President's communications and activities, related to the performance of duties under that Article,” Burger said.

In the end, the Burger Court said that “absent a claim of need to protect military, diplomatic, or sensitive national security secrets, we find it difficult to accept the argument that even the very important interest in confidentiality of Presidential communications is significantly diminished by production of such material.”

The Burger decision also made it clear that the Court could decide the issue, citing another landmark case, Youngstown Sheet & Tube, and Justice Robert Jackson’s concurring opinion. “The Framers of the Constitution sought to provide a comprehensive system, but the separate powers were not intended to operate with absolute independence,” Burger’s opinion said. He then pointed to a quote from Jackson’s opinion: “While the Constitution diffuses power the better to secure liberty, it also contemplates that practice will integrate the dispersed powers into a workable government.”

In the United States v. Burr case, President Jefferson said that Marshall’s decision was wrong, but he would voluntarily supply the documents. This was a typical reaction from most Presidents confronted with such requests.

Former Watergate prosecutor and Harvard law scholar Archibald Cox detailed the history of these encounters in a law review article updated in 1974 just after the Watergate Tapes decision. By Cox’s estimate, there were 20 occasions where 13 Presidents between the George Washington and John F. Kennedy administrations refused to turn over information to Congress. In some cases, Presidents had legitimate confidentiality reasons for withholding information or there wasn’t a clear mandate from Congress.

Other examples included a decision in 1796 by President Washington related to a House request for documents related to the controversial Jay Treaty. Washington decided that the House didn’t have a right to see the documents because it didn’t consent to treaties. Instead, he sent them to the Senate. Only two Presidents, Andrew Jackson and Theodore Roosevelt, withheld information from Congress on what Cox said were grounds that couldn’t be easily justified.

A 2014 research report from the Congressional Research Service looks at what happens when there has been a conflict over executive privilege between the President and Congress that has spilled over into the courts. “Few such inter-branch disputes over access to information have reached the courts for substantive resolution. The vast majority of these disputes are resolved through political negotiation and accommodation,” the CRS said in late 2014.

“There have been only four cases involving information access disputes between Congress and the executive, and two of these resulted in decisions on the merits,” it said. But since the Eisenhower era, every presidential administration through the Obama era has asserted executive privilege at least once when presented with a request from Congress

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.