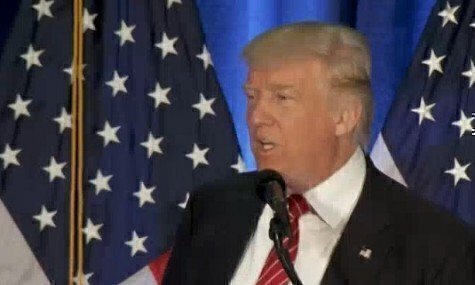

On Monday, Republican presidential nominee Donald J. Trump proposed a new set of questions to be presented to immigrants, in an attempt to screen out people who may potentially be a threat to American security.

“A Trump Administration will establish a clear principle that will govern all decisions pertaining to immigration: we should only admit into this country those who share our values and respect our people,” the candidate said in a major foreign policy speech.

“In addition to screening out all members or sympathizers of terrorist groups, we must also screen out any who have hostile attitudes towards our country or its principles – or who believe that Sharia law should supplant American law. Those who do not believe in our Constitution, or who support bigotry and hatred, will not be admitted for immigration into the country,” Trump added.

Whether the proposed questions are eventually added to an already complicated immigration process remains to be seen. But in looking back at the history of immigration to the United States, tests and criteria have been a frequent factor in considering admission to this country. And adherents to some political and moral philosophies have consistently been barred from entry to America.

In our form of constitutional government, Congress has the authority to decide who may become a citizen or reside in the United States. Congress set the first basic immigration requirement in 1790, which required a two-year residency in the United States for those who sought citizenship.

In 1875, the first direct immigration-criteria law, the Page Act, came from Congress. It declared that people and groups could be excluded as immigrants based on specific criteria. Initially, prostitutes and criminals were banned from entry, and port inspectors were appointed to question and screen immigration candidates.

The Chinese Exclusion Acts, passed by Congress and signed into law by President Chester Alan Arthur in 1882, at first barred Chinese laborers from entering the United States, and these restrictions were expanded to many ethnic Chinese, regardless of nationality, in subsequent laws.

The Immigration Act of 1891 expanded the list of "undesirables" to include “idiots, insane persons, paupers or persons likely to become a public charge,” persons suffering from certain contagious disease, felons, persons convicted of other crimes or misdemeanors related to “moral turpitude,” and polygamists. (FYI, current immigration laws still bar moral turpitude offenders.) In 1903, an immigration act signed by President Theodore Roosevelt added anarchists to the banned list and the act allowed immigration officials to ask people about their political beliefs during the questioning process.

For example, a person arriving at Ellis Island in 1905 would face several tests before gaining admission to the United States. A medical test often proved most challenging to some immigrants, along with cognitive testing.

In the February 1905 edition of Popular Science, Dr. Allan McLaughlin from the U. S. Public Health and Marine Hospital Service explained the testing process. Immigrants who weren’t first class passengers were diverted through Ellis Island for inspections and checked by medical personnel. If they passed that screening process, the immigrants were then quizzed by clerks accompanied by interpreters.

“The clerk, or interpreter, interrogates each alien, and finds his name, and verifies the answers on the manifest sheet before him, and if, in the opinion of the immigrant inspector, the immigrant is not clearly and beyond doubt entitled to land, he is held for the consideration of the board of special inquiry,” McLaughlin said.

The list of 1905 manifest questions included confirmation that the person had at least $30 on their person and if they had ever been in a prison or an institution. And immigrants were asked if they were anarchists or polygamists.

In 1917, another act combined all the previously defined excluded groups in one do-not-admit list; added alcoholics to the list; required literacy tests; and banned people from many parts of the Asia-Pacific region, and in 1924, quotas were set for immigration based on countries of origin, and Japan was effectively added to the do-not-admit list.

By the 1950s, immigration exclusion laws changed to lift the ban on Chinese immigration, and the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act eliminated immigrants who advocated “the economic, international, and governmental doctrines of world communism.” (President Harry Truman vetoed the McCarran-Walter Act, but Congress overrode the veto.)

Since then, the immigration system has grown more complex, but there are still some basic criteria left from older exclusion legislation.

In overall terms, the Immigration and Naturalization Act provides for an annual worldwide limit of 675,000 permanent immigrants, with exceptions for close family members. Potential immigrants are evaluated based on family, employment, refugee and country-of-origin criteria.

According to the latest State Department rules on which criteria make potential immigrants ineligible for visas under the INA, people can be excluded if they have certain health conditions or have a criminal record.

Potential immigrants found to have terrorist ties are also excluded, including anyone who “endorses or espouses terrorist activity or persuades others to endorse or espouse terrorist activity or support a terrorist organization.”

Anyone who is a current member of a totalitarian party is still excluded, such as “any immigrant who is or has been a member of or affiliated with the Communist or any other totalitarian party (or subdivision or affiliate thereof), domestic or foreign.” There are provisions to allow former party members to come to the United States as immigrants, based on how long ago they ceased their party membership and if they lived in a nation where the ruling government prescribed party membership.

And the ban placed on polygamists back in 1891 still stands.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.