Constitution Daily looks at two “what if” scenarios that would have given us 10 different presidents through history. What factor would have given us Samuel Tilden, Willie Mangum or Aaron Burr as the nation’s leader?

As written in 1787, the Constitution gave a broad outline of how the presidency changed hands in elections, or through the process of succession by statute or constitutional amendment.

Four constitutional amendments refined this process. The 12th Amendment dealt with the disputed election of 1800, which ended in a tie when presidential and vice-presidential candidates were allocated the same Electoral College votes.

The 20th Amendment had provisions for candidates elected but not yet sworn into office. The 22nd Amendment limited presidential terms to two terms.

The 25th Amendment ratified in 1967 cleared up any questions about the vice president’s ability to succeed a President who dies in office, who resigns, or who is removed from office.

Until 1967, the succession rules were based on a loosely defined Article II, Section 1, of the Constitution; a precedent set by President (or Acting President, as his opponents believed) John Tyler in 1841; and a presidential succession law passed by Congress that named the next-in-line to the White House after the president and vice president.

Without these changes, the swing of a few votes in the general election or in the House, or a decision by a special commission or the Supreme Court, the White House might have had a few different occupants, who are little-known to Americans today.

Also, some presidents avoided extreme physical danger and remained in office.

By Election

Aaron Burr. The bitterly contested 1800 presidential election between Thomas Jefferson and John Adams became a constitutional crisis after a mistake left Jefferson tied with his running mate, Burr, in the Electoral College election. Burr then decided to run for president in the House runoff election against his own running mate. Burr lost on the 36th ballot in the House due to the influence of Alexander Hamilton.

Samuel Tilden. Tilden won the popular vote in the 1876 election against Rutherford B. Hayes, but four southern states had two rival sets of electors, putting the presidential election in limbo. The actions of a special commission of Congress and Supreme Court members headed off a constitutional crisis, as Hayes took the election by one electoral vote.

Winfield Scott Hancock. In the often forgotten 1880 election, General Hancock lost to James Garfield by the closest popular vote margin in history, 0.09 percent., or 1,898 votes. Each candidate won 19 states, but Hancock, a Pennsylvanian and a Democrat, couldn’t win most northern states, and he lost by 56 electoral votes.

Charles Evans Hughes. On Election Night, Hughes went to bed thinking he won the election against his opponent, President Woodrow Wilson. The former Supreme Court justice later found out that California went to Wilson by 3,773 votes, costing Hughes the White House.

By Succession

Willie P. Mangum. If Mangum’s name doesn’t seem familiar, that’s because he was the Senate president pro tempore in 1844. Between 1792 and 1886, the president pro tempore was second-in-line to the White House, after the Vice President.

After the passing of President William Henry Harrison in 1841, John Tyler assumed the presidency by boldly declaring he was entitled to the full power and title of President.

But Tyler himself was nearly killed in a shipboard explosion in 1844. President Tyler was stopped by a dignitary on his way up to a deck to witness a naval gun display on the USS Princeton. The gun exploded, killing the Secretary of State and the Secretary of the Navy instead.

Lafayette S. Foster. Foster was the Senate president pro tempore in 1865 when Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. Part of the plot to kill Lincoln included an assassination attempt on Vice President Andrew Johnson.

John Wilkes Booth had convinced George Atzerodt to kill Johnson at a hotel where the vice president was staying. Atzerodt camped out in a room above Johnson’s room, but he decided on a fateful night to abandon the attempt, and he went out drinking instead. Had he killed the unsuspecting Johnson, Foster would have been acting president, until an election could be held to choose a new President in December 1865.

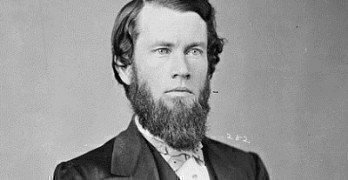

Benjamin Wade. It was Wade who had replaced Foster as Senate president pro tempore by 1868 when President Andrew Johnson was impeached by the House and put on trial in the Senate.

One of the theories about how Johnson escaped a guilty verdict, by one vote, in the Senate was that there was a contingent of Senators who didn’t want Wade, who was a radical Republican, as acting president. Said one newspaper at the time: “Andrew Johnson is innocent because Ben Wade is guilty of being his successor.”

Thomas W. Ferry. Ferry’s brush with the presidency was more of a theoretical one but all too real under the election laws of 1876 during the Tilden-Hayes election.

Congress appointed a 15-person commission, including five Supreme Court Justices, to settle the disputed race. The commission ruled in favor of Hayes just two days before the inauguration. Ferry was the Senate president pro tempore at the time and he would have been the Acting President if the Electoral College vote wasn’t certified on March 4, 1877

John Nance Garner. Garner almost became president under the terms of the 20th amendment ratified just weeks before an assassination attempt on President-Elect Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 The 20th Amendment was ratified on January 23, 1933, and it made provisions for the vice president-elect, in this case, Garner, to assume the presidency if the president-elect died before taking the oath of office.

On February 13, 1933, just 23 days after the amendment went into force (and 17 days before Roosevelt’s inauguration), Giuseppe Zangara opened fire on a car in Miami that contained President-Elect Roosevelt. He missed Roosevelt but fatally wounded Chicago mayor Anton Cermak.