In honor of our new food exhibit at the National Constitution Center, we look at 10 famous Supreme Court decisions directly or tangentially related to tomatoes, eggs, milk, apple cider vinegar and raisins.

If you are in the Philadelphia area, our “What’s Cooking, Uncle Sam?” exhibit showcases examples of how government regulations, research, and economics have shaped what we eat and why.

If you are in the Philadelphia area, our “What’s Cooking, Uncle Sam?” exhibit showcases examples of how government regulations, research, and economics have shaped what we eat and why.

And with all things related to society, at some point a disagreement over the composition, distribution and regulation of food, vegetables and drinks will make its way to the Supreme Court.

Here are 10 famous examples of cases in which the nine Justices tackled these questions.

Nix v. Hedden (1893)

The high court faced an early case of food jurisprudence by answering a crucial question: Is a tomato a fruit or a vegetable? A unanimous Court, led by Justice Horace Gray, decided that for customs purposes, tomatoes should be considered as vegetables, even though botanists said they were fruits.

“Botanically speaking, tomatoes are the fruit of a vine, just as are cucumbers, squashes, beans, and peas. But in the common language of the people, whether sellers or consumers of provisions, all these are vegetables which are grown in kitchen gardens, and … usually served at dinner in, with, or after the soup, fish, or meats which constitute the principal part of the repast, and not, like fruits generally, as dessert,” wrote Gray.

Hipolite Egg v. United States (1911)

The Supreme Court upheld the Pure Food and Drug Act as a proper use of Congress's power to regulate interstate commerce. The eggs in question were canned but adulterated and had crossed state lines.

U.S. v. Lexington Mill and Elevator Company (1914)

The Supreme Court takes on food additives. It says bleached flour with nitrite residues can’t be banned from foods unless the government can show the additive causes harm. But it confirms that food containing deleterious ingredients are illegal when they cause injury.

U.S. v. 95 Barrels Alleged Apple Cider Vinegar (1924)

The Court says that a product called "Apple Cider Vinegar Made from Selected Apples" was misleading because it was made from dried apples, and the vinegar was misbranded under the Food and Drugs Act.

“The words 'made from selected apples' indicate that the apples used were chosen with special regard to their fitness for the purpose of making apple cider vinegar. They give no hint that the vinegar was made from dried apples, or that the larger part of the moisture content of the apples was eliminated and water substituted therefor. As used on the label, they aid the misrepresentation made by the words 'apple cider vinegar,”” says Justice Pierce Butler.

Schechter Poultry v. United States (1935)

On its face, Schechter Poultry was about the alleged sale of sick chickens and the ability of the executive branch to stop it. In reality the case was about the Live Poultry Code, which was written by the FDR administration. The code fixed the maximum number of hours a poultry employee could work, added minimum wages for the workers, and controlled methods of "unfair competition."

The Supreme Court, with Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes writing the majority decision, said the Code wasn’t a valid exercise of Commerce Clause power reserved to Congress. The decision also nullified an important New Deal program, the National Industrial Recovery Act.

United States v. Carolene Products (1938)

The case was about a law passed by Congress called the Filled Milk Act, which barred interstate shipments of skimmed milk compounded with fats or oils other than milk fat. But it is best known today for its “Footnote Four,” a footnote added by Justice Harlan Stone, that said the Court should review laws more closely if they discriminated against “discrete and insular minorities” that didn’t have the political power to defend themselves.

Wickard v. Filburn (1942)

The Wickard case was about government-imposed wheat production quotas during the end of the Great Depression that were designed to control wheat prices. Filburn, a farmer, grew more wheat than allowed, and was fined. He claimed he was keeping the excess wheat for his own use, and not selling it as a product. A unanimous court said that Congress had powers to enable Filburn to be fined, under the Interstate Commerce Clause, because even the use of home-grown products could affect market conditions.

Gallagher v. Crown Kosher Super Market of Massachusetts, Inc. (1961)

In this religious liberties case, Chief Justice Earl Warren, writing the majority decision, said that Sunday closing laws must apply to Orthodox Jewish who were shopkeepers. The shopkeepers complained on various First Amendment and equal protection grounds. Warren and five other Justices ruled that the laws were “not regarded as religious ordinances.”

POM Wonderful v. Coca-Cola Co. (2014)

This recent dispute is over pomegranate juices between Coca-Cola’s Minute Maid division and POM Wonderful, which makes various pomegranate products. POM Wonderful claimed a Lanham Act trademark violation was incurred by Coca-Cola, based on the premise that small amount of pomegranate juice in the competitive Minute Maid product was misleading and presented unfair competition. Coca-Cola cited the FDA’s power to control food and beverage labeling as a controlling factor.

A unanimous Court sided with POM Wonderful, deciding that it could pursue legal action.

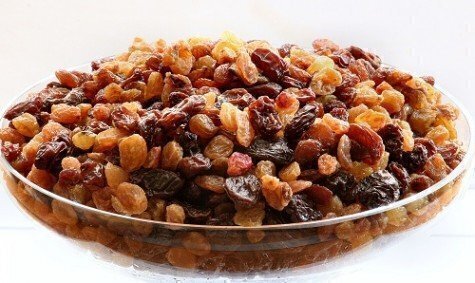

Horne v. Department of Agriculture (2015)

The Horne case was about the government’s ability to regulate raisin crops and the Fifth Amendment. At the heart of the argument was the Raisin Marketing Order, which dates back to the Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act of 1937. The order required growers to turn over a percentage of handled raisins to the federal government. The government removed surplus raisins from the market to regulate raisin prices, and often resold part of its confiscated raisin horde to the market, giving some proceeds back to the growers. Marvin Horne, the farmer in the case, was fined $695,000 for noncompliance with the order.

A split Court held that the move to confiscate the excess raisins was a taking under the Fifth Amendment and Horne was due just compensation.