The mother of all political campaign debates was the battle between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, and by today’s standards, our modern debaters would be challenged to fit the 1858 format.

For example, in tonight's debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, moderator Lester Holt will preside over six segments of approximately 15 minutes each on major topics to be selected by Holt and announced at least one week before the debate. Each candidate will get two minutes to respond to Holt's specific questions and then have an opportunity to respond to each other.

During the seven Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858, the first speaker talked for one hour, followed by a 90-minute rebuttal from the second speaker, and a 30-minute closing statement from the first speaker.

And the environment wasn’t genteel. Partisan supporters were in the crowds, some of which were over 10,000 people as the two men argued their positions as part of a campaign for a U.S. Senate seat from Illinois. (Back then, votes were cast for state legislators, who then named a Senator to send to Washington.)

There are debate transcripts and numerous press accounts of the seven debates, which drew national attention as they confronted the issues of slavery and the 1857 Dred Scott decision by the Supreme Court.

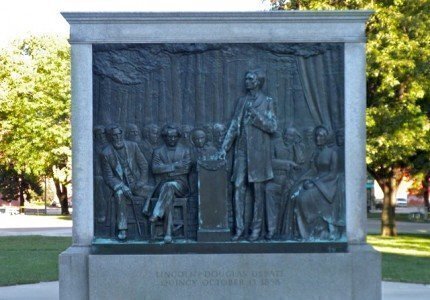

Here are some memorial moments from the debates, along with some words that transcended the arguments.

Lincoln framed the debate’s arguments before they began. Lincoln asked for his party’s nomination in June 1858 with his famous “House Divided” speech. “‘A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe the government cannot endure, permanently, half slave and half free,” he said.

Douglas countered with his own public speech that labeled Lincoln as a dangerous radical. “Mr. Lincoln advocates boldly and clearly a war of sections, a war of the North against the South, of the free States against the slave States- a war of extermination -to be continued relentlessly until the one or the other shall be subdued, and all the States shall either become free or become slave,” Douglas said, referring to Lincoln’s “House Divided” comments. Soon after this, Lincoln challenged Douglas to a series of seven debates within Illinois.

The debates started in Ottawa, Illinois, on August 21, 1858 as a crowd of about 10,000 people attending despite the hot weather. “I appear before you to-day for the purpose of discussing the leading political topics which now agitate the public mind,” Douglas says in his opening statement.

After praising Lincoln and explaining he had known Lincoln for 25 years, Douglas went on the attack and said Lincoln opposed the American effort in the Mexican War; Lincoln supported a radical anti-slavery GOP platform; and Lincoln didn't understand the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision. Lincoln’s response: “When a man hears himself somewhat misrepresented, it provokes him - at least, I find it so with myself; but when misrepresentation becomes very gross and palpable, it is more apt to amuse him.”

The remaining debates covered the problem of slavery, its extension into new states, the rights of African-Americans and the possibility of a sectional war over these issues. Lincoln often referred to the Declaration of Independence in making his arguments that slaves and blacks had some rights under the Declaration.

“I agree with Judge Douglas he is not my equal in many respects—certainly not in color, perhaps not in moral or intellectual endowment. But in the right to eat the bread, without the leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, he is my equal and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every living man,” Lincoln said.

Douglas countered that the Declaration didn’t apply to blacks, but Lincoln forced Douglas into a corner in the second debate, when he got Douglas to acknowledge that some states could decide to bar slavery within their own borders.

Lincoln then seemed to master his debate tactics and was putting Douglas on the defensive as the series concluded. In a debate at Knox College in front of 25,000 people, Lincoln said, “Judge Douglas declares that if any community want[s] slavery, they have a right to have it. He can say that, logically, if he says that there is no wrong in slavery; but if you admit that there is a wrong in it, he cannot logically say that anybody has a right to do wrong."

In the concluding remarks of the last debate, Douglas stood by his views that states could determine their own slavery status. “All you have a right to ask is that the people shall do as they please; if they want slavery let them have it; if they do not want it, allow them to refuse to encourage it,” he said.

Douglas continued to argue that a radical proposition of ending slavery was unconstitutional and a pretext for sectional violence. “Suppose one section makes war upon any other peculiar institution of the opposite section, and the same strife is produced. The only remedy and safety is that we shall stand by the Constitution as our fathers made it, obey the laws as they are passed, while they stand the proper test and sustain the decisions of the Supreme Court and the constituted authorities.”

In the end, the Illinois state legislature elected Douglas over Lincoln, although a modern analysis of the voting showed Lincoln had more popular votes. But the national publicity over the debates instantly made Lincoln a leading figure in the Republican Party.

Two years later, both men ran for President. While there were no debates in 1860, the edited transcripts of the 1858 debates were used during the campaign. Lincoln won the election after the Democratic Party, like a House Divided, fielded two candidates.