The internet has pushed legal boundaries—and created new ones—since it was first unveiled to the world in 1991. It has raised questions and sparked legal activity around the issues of free speech, censorship, privacy, and, most recently, equality.

Much of the debate around equality on the web has centered on the term “net neutrality,” which, simply put, is the premise that all internet traffic is created equal. In practice, this translates to the idea that internet service providers (ISPs)—companies like Comcast, Verizon, and Time Warner Cable—should treat all internet traffic equally.

On June 14, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit made a two-to-one decision to uphold the authority of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to enforce the principle of net neutrality. However, the road leading to the recent decision was fraught with conflict and the aftermath is likely to be the same.

The battle over net neutrality has been a long one fought primarily between the FCC and large internet service providers. The term itself was coined in a paper by Columbia University law professor Tim Wu in 2003 but was little more than just a term until 2010, when the FCC passed the Open Internet Order. The order called for ISPs to honor the principle of net neutrality through transparency on network management practices, refraining from blocking content on their networks, and avoiding unreasonable discrimination against (or favorable treatment towards) content on their networks.

The issue with enforcing this Order, however, came from a 2005 Supreme Court decision classifying cable internet as an information service. This ruling meant that the FCC, the overarching regulatory body of telecommunication services, could not regulate cable internet because its classification did not fall under the FCC’s supervisory jurisdiction. The discrepancy came to light in Verizon Communications Inc. v. FCC (2014), in which Verizon argued that the FCC was overstepping the bounds of its authority. The D.C. Circuit struck down the Open Internet Order, and the FCC was forced to go back to the drawing board.

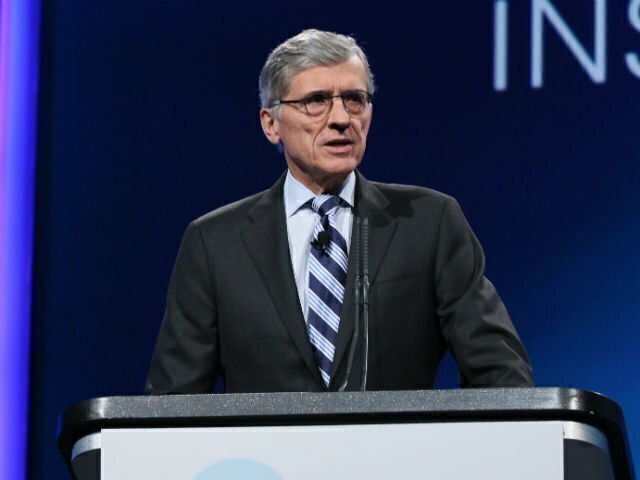

In May 2014, FCC chairman Tom Wheeler spearheaded an attempt to generate guidelines for new open internet rules and opened them up for public debate and civilian input. “It’s the most powerful and pervasive platform on the planet,” he said. “The internet is too important to allow broadband providers to make the rules.”

Wheeler’s guidelines were used to craft a new proposal that was finally put to a vote in February 2015 and passed by a 3-2 majority on the commission. The new rules reclassified broadband as a utility under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934, making ISPs “common carriers” subject to the same regulation as telecommunication services. This “common carrier” distinction was extended to mobile networks as well. The rules also prohibited the practices of internet “fast-lanes,” in which ISPs effectively play favorites and preferentially speed up certain provider content, and paid prioritization, in which content providers pay ISPs to get their customers faster service.

The new rules officially went into effect on June 12, 2015, but debate and legal skirmishes between the FCC and big names in internet service have spanned the last decade, three times resulting in lawsuits. Last week’s ruling is the most recent standoff, in which multiple cable, internet and mobile service providers again leveled a petition against the FCC challenging the validity of its latest Open Internet Order.

In its ruling, the D.C. Circuit panel validated the reclassification of broadband as a utility, thereby placing internet (and mobile) service providers under the same umbrella as telecommunication services. It definitively gave the FCC the legal authority to enforce net neutrality in those arenas. The majority opinion’s argument hinged on the reclassification of broadband as a telecommunication service; by doing so, the FCC was able to bring ISPs under its jurisdiction. The opinion also emphasized the importance of ensuring unfettered internet access, given the immense reach and impact of the internet as a tool for communication and means of accessing information.

The dissent, however, argued that the regulations to which ISPs would now be subject at the hands of the FCC were an “unreasoned patchwork” that would have detrimental effects on the competitive business climate. The regulations have the potential to present direct harm to the well-being of the companies themselves.

Why is net neutrality such a contentious subject? Consider the issue from multiple perspectives.

As a consumer, net neutrality guarantees that I receive my web content at the same speed and with the same degree of access as everyone else.

As a producer, I can create a website or online startup and know that it is immediately accessible to any internet user in the world. I do not have to pay ISPs more to make sure that my content loads as quickly or works as well as that of an established company. This creates an atmosphere ripe for innovation and competition: new competitors are always able to enter the marketplace and vie for success, and there is a constant exchange and influx of new ideas and concepts via the web.

As a content provider, the prohibition of fast lanes means that my competition cannot get a leg up by paying ISPs extra for faster service to their customers. It means that ISPs cannot charge me extra for streaming high volumes of content. However, it also means that I am unable to give myself a competitive advantage by paying ISPs to provide my customers with faster service.

As an ISP, the prohibition of paid prioritization and fast lanes is a direct threat to my company’s ability to be competitive. It neutralizes my ability to jockey with other ISPs to strike deals with lucrative content providers and stifles the market. Furthermore, even if they take up significant internet traffic, the burden of the extra costs to accommodate content providers effectively falls upon my company.

The worry, expressed both in the recent dissenting opinion and in the February 2015 FCC vote, is that overregulation can lead to stagnation of a competitive landscape in internet service provision, which could create the very monopolistic atmosphere that net neutrality aims to combat. If everyone receives equal treatment, then giants remain giants and new entries to the service provision field will have difficulty gaining traction. However, a competing concern is that, if left to their own devices, ISPs would change internet access from a utility into a commodity, slowing service to some users and speeding it up for the highest bidders.

These are the core grievances at the heart of what will undoubtedly continue to be a heated battle over net neutrality. If there is a way to toe the line between guaranteeing an open and equal internet while avoiding over-regulation and the potential stagnation of market competition, only time—and many more appeals—will tell.

Jordyn Turner is an intern at the National Constitution Center. She is also a recent graduate of Dartmouth College, where she majored in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies and minored in Government. This fall, Turner will begin work toward a master’s degree in Global Studies from Tsinghua University in Beijing as a member of the inaugural class of the Schwarzman Scholars Program.