Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center’s constitutional literacy adviser, looks at the question whether Americans taking overseas journeys have American legal protection to accompany them.

THE STATEMENT AT ISSUE:

THE STATEMENT AT ISSUE:

“The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act shields foreign states and their agencies from suit in United States courts unless the suit falls within…enumerated exceptions. This case concerns the scope of the commercial activity exception….Carol Sachs is a resident of California who purchased in the United States a Eurail pass for rail travel in Europe. She suffered traumatic personal injuries when she fell onto the tracks at the Innsbruck, Austria, train station while attempting to board a train operated by the Austrian state-owned railway. She sued the railway in federal district court, arguing that her suit was not barred by sovereign immunity…because it is based upon the railway’s sale of the pass to her in the United States…We disagree….All of her claims turn on the same tragic episode in Austria, allegedly caused by wrongful conduct and dangerous conditions in Austria, which led to injuries suffered in Austria.

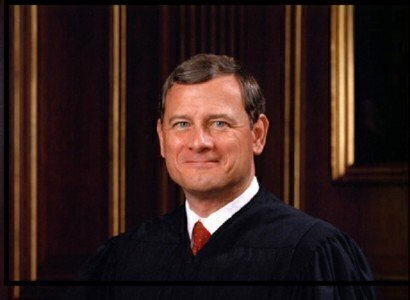

– Excerpt from a Supreme Court decision on December 1, ending a damages lawsuit in a U.S. court by an American tourist who lost both legs above the knees in an accident in Austria. The case was OBB Personenverkehr AG v. Sachs. The unanimous decision was written by Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr.

WE CHECKED THE CONSTITUTION, AND…

Borrowing from the Declaration of Independence, calling for the institution of a new government in America, to have “separate and equal status” among the nations, those who wrote the Constitution in Philadelphia put together the architecture of a sovereign government. Sovereignty, a concept originating in the unchallengeable prerogative of royalty, gave the new government of the people the right to stand alone in the world. The original document is permeated with claims of sovereign authority – such as the power to wage war.

But one of the limitations of one nation’s sovereignty is that, in affairs between countries, it must also respect the sovereignty of others. One of the questions that the U.S. Supreme Court has found that it must repeatedly ask and answer is how far to extend the American government’s power out into the world at large.

A famous series of cases in the early 1900s, when America was just beginning to be a colonial power, involved whether the Constitution should extend outside the U.S. borders. Those decisions came in the so-called “Insular Cases.”

But this is not a phenomenon of the past. The Supreme Court in 2008 relied heavily upon its understanding of the Insular Cases in deciding that foreigners being held at the U.S. Navy prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, should have the benefit of at least some constitutional rights. Today, a Mexican family has a case before the Supreme Court claiming that their son’s rights under the American Constitution were violated when a U.S. Border Patrol agent shot across the border, killing the boy. The Mexican government supports the family, partly on the premise that such cross-border incidents impinge on its national sovereignty and its duty to protect its own citizens.

In the community of nations, respect for sovereignty must be a mutual undertaking, and any attempt to hail another government into one nation’s courts is always at least a potential compromise of that comity. That is why, when Congress in 1976 formalized the long-honored tradition of requiring U.S. courts to acknowledge legal immunity for other sovereigns, the law included fairly narrow exceptions. (The law is the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act.)

The Supreme Court, in a series of decisions in recent years, has also repeatedly put limits on the enforcement of U.S. laws beyond the nation’s own borders. That is not only a limit on federal legislative power, but also a gesture of respect for other nations’ right to govern themselves.

Another example of the extreme sensitivity of mutual respect among nations was the deep anger expressed by many of America’s closest allies when they discovered, through leaks of secret information, that the U.S. government’s global telephone surveillance program had been monitoring the private communications of foreign leaders.

But in a world that has become a global village, in which people travel more or less freely across national borders and move around with ease inside many countries, the question arises of whether Americans taking such journeys have American legal protection to accompany them.

A just-issued Supreme Court decision illustrates the question, and how it got answered in at least one instance. This was the case of a California tourist who was gravely injured in a railroad accident in Austria. Her case has now been scuttled by the court, in a unanimous ruling finding that the case would intrude on Austrian sovereignty because it had an inadequate connection to the United States.

While the case focused on one American and one incident, it may well have larger meaning. When U.S. tourists go to Europe, they often find that the easiest way to get around within and among countries is to go by rail. That means that they will be passengers, throughout Europe, on government-run railways. And any mishaps that occur may well be the fault of the way those railroads are run.

Few of these tourists, however, would be likely – in advance of their trip – to try to buy tickets directly from the foreign railroad. Customarily, and for greater convenience, they probably would go through a ticket agency in this country, as Californian Carol Sachs did.

What she and other would-be travelers by Eurail have now discovered is that, unless a foreign railroad actually sets up shop in some way inside the U.S., establishing a commercial presence that would put them within reach of U.S. laws (in Carol Sachs’ case, the state laws of California), the railroad could rarely, if ever, be held accountable for causing injuries, or worse.

That may well be a personal tragedy, in cases like Carol Sachs’. And it probably is of little comfort that this is one of the prices to be paid for good relations among nations – including America.